By Charlton Bannister, Analysis and Insights Manager at ORE Catapult

Grimsby, a town on the east coast of England, has seen a revolution. Once the largest fishing port in the world, it saw a steep decline during the cod wars between Britain and Iceland in the 1970s. However, a new maritime industry is quickly taking the place of fishing and Grimsby is now a thriving industrial hub and one of the busiest ports in the world for wind farm support vessels. Ships bristling with skilled engineers and the latest technology leave port to build and fix the turbines supplying green energy to the UK.

Because of this, Grimsby is a leading force in supporting the UK to reduce its CO2 emissions to meet the commitments it made in the 2015 Paris climate agreement (designed to limit temperature increases to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels). Electricity from power stations, going to homes and businesses across the UK, accounts for 20% of total energy use so decarbonising this sector is critical.

To meet their targets, the UK has invested in renewable electricity generation, most notably wind energy which is booming, and propelling the UK toward reaching its goals.

CfDs

The most important tool used by the UK Government to incentivise the building of wind turbines has been the Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme. The scheme provides wind turbine owners with a fixed price for their electricity over 15 years. This is similar to fixing the interest rate on your mortgage.

For the fixed rate period, no matter the changes to interest rates in the market, the same rate is paid every month. For the turbine owner, they receive a fixed amount per unit of electricity produced (government guaranteed), no matter what the market price of energy is. These units are Mega Watt hours (MWh), and the average UK household uses 3.7 MWh of electricity a year.

CfDs have two main objectives. The first is to support the development of wind energy in the UK. The second is to bring the cost of wind energy down using an auction where developers bid for CfDs at the lowest price to win. They have worked well in both areas:

- The UK is generating 70% more energy from wind in 2022 than it did in 2017. This success has changed the nature of the electricity market in the UK. On some days, up to 45% of UK electricity demand is met by wind energy, and overall, it provided 26.8% of the UK’s energy in the last year[1].

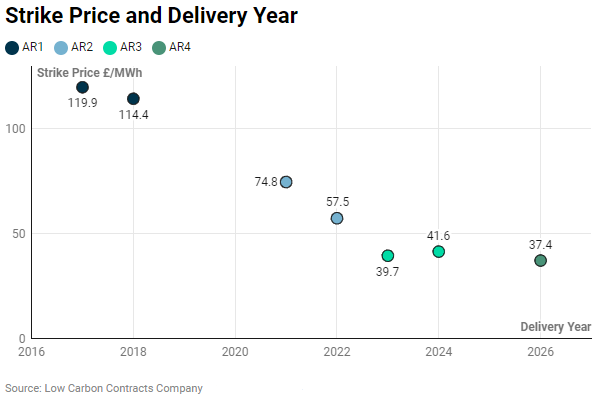

- CfDs have helped to reduce the cost of offshore wind energy by more than two thirds, from £119.9/MWh to £39.7 from 2017 to 2023 (see below graph)[2]. This means that in 2022, electricity from wind was one quarter the wholesale price of electricity, saving consumers millions of pounds.

*Prices in the above table are in 2012 terms

Challenges faced by the wind energy sector

This shift in the cost and deployment of wind generation has had several knock-on effects. It is likely that offshore wind energy in the UK is as cheap as it is going to get. At the same time, the scale of wind deployment in the UK has created some issues for the energy system.

CfDs are released in rounds, the last round being Allocation Round 4 (AR4) in 2022. The next round (AR5) is due to happen later this summer. The industry is predicting that CfD prices may stay the same as they were in AR4, or even increase. This contrasts with the consecutive decreases observed previously (see above graph), driven by a rapid increase in the size of turbines, increased efficiency in manufacturing, reduced cost of finance/insurance, and more efficient Operations and Maintenance strategies. The industry is now more vulnerable to cost increases from external factors, such as cost of labour, parts and raw materials.

The number of turbines the UK has installed and the large amounts of energy they produce has had significant impacts upon the energy system. Ten years ago, power generation was centred on coal, gas, and nuclear power plants, located near centres of energy demand, such as London. However, wind turbines need to be located where it is windy – outside of large cities. The grid was not developed to service this generation, and it is a long and complex process to develop it. It works like a series of water pipes – the further away the generator is, the more pipe you need to build. The bigger the generator, the thicker the pipe needs to be, and it is only possible to push so much water through the pipe.

Wind energy is also intermittent and turbines only generate when it is windy. Previously, when wind was generating, the capacity of other power plants could be turned down, and when it was not, they could be turned back up again. However, when 30% of the energy comes from wind annually, the grid cannot sustain this variability without incurring large costs.

Then, there is the growing challenge of component availability. Despite the UK being the leading wind generator in Europe, much of the manufacture of components for turbines happens elsewhere. This means that the UK is losing potential jobs and revenue. Security of supply also becomes harder to ensure, as parts produced overseas can be stopped from reaching the UK due to political or logistical issues.

The CfD is therefore facing challenges. Forcing turbine owners to compete on price, when they already have very low margins, is slowing down the deployment of wind energy. The CfDs do not incentivise owners to fix some of the problems regarding their location and timing. The UK is not capturing the value from wind turbine components.

NPFs

Non Price Factors (NPFs) could hold the solution. These are factors against which CfD applicants could be scored, other than price. There are several different ways the government might introduce NPFs to the CfD system, and these factors could be considered as part of a CfD application. If the NPFs in a CfD bid created positive effects, it would increase the likelihood of success by increasing the value of their bid. There are several different factors that could be considered.

Applicants with plans to develop and improve the UK supply chain for delivering wind farms would improve their value. This might include investing in manufacturing and port capacity in the UK, investing in onshore and offshore grid capacity, or improving the sustainability of the supply chain. The strength of each applicant’s business case in this area would be compared against other applicants’ bids.

Plans to help reduce the impact of the timing and location of wind turbines would be viewed positively. This might include investing in batteries to sit alongside wind farms that could be charged at times where the grid could not handle the electricity generated from the farm, and discharged when power was required through the grid (like a water tank in a series of pipes).

However, there are challenges in implementing NPFs. They would make the already complex process of bidding for CfDs, even more difficult. It is also tricky to determine what value would be attributed to the NPFs and participants might try to “game” the bidding process. So NPFs may be difficult to implement, but it is clear that something has to change.

The full potential of UK development of offshore wind has been demonstrated in Grimsby, which has witnessed the pace and scale of change in renewables over the past decade . Wind farm developers and operators Ørsted and RWE have both invested to expand and upgrade the port facilities. Ørsted has put £10m into their Operations and Maintenance facility in the area, employing over 370 workers[3]. Ultimately, this has been driven by the government through the CfD scheme. But now the UK is reaching a turning point. The grid and CfD markets no longer operate as they once did. It is time to adapt and push on to meet the net zero goals critical to our success.

[1] Figures from: electricinsights.co.uk

[2] Low Carbon Contracts Company

[3] orsted.co.uk/energy-solutions/offshore-wind/transforming-communities